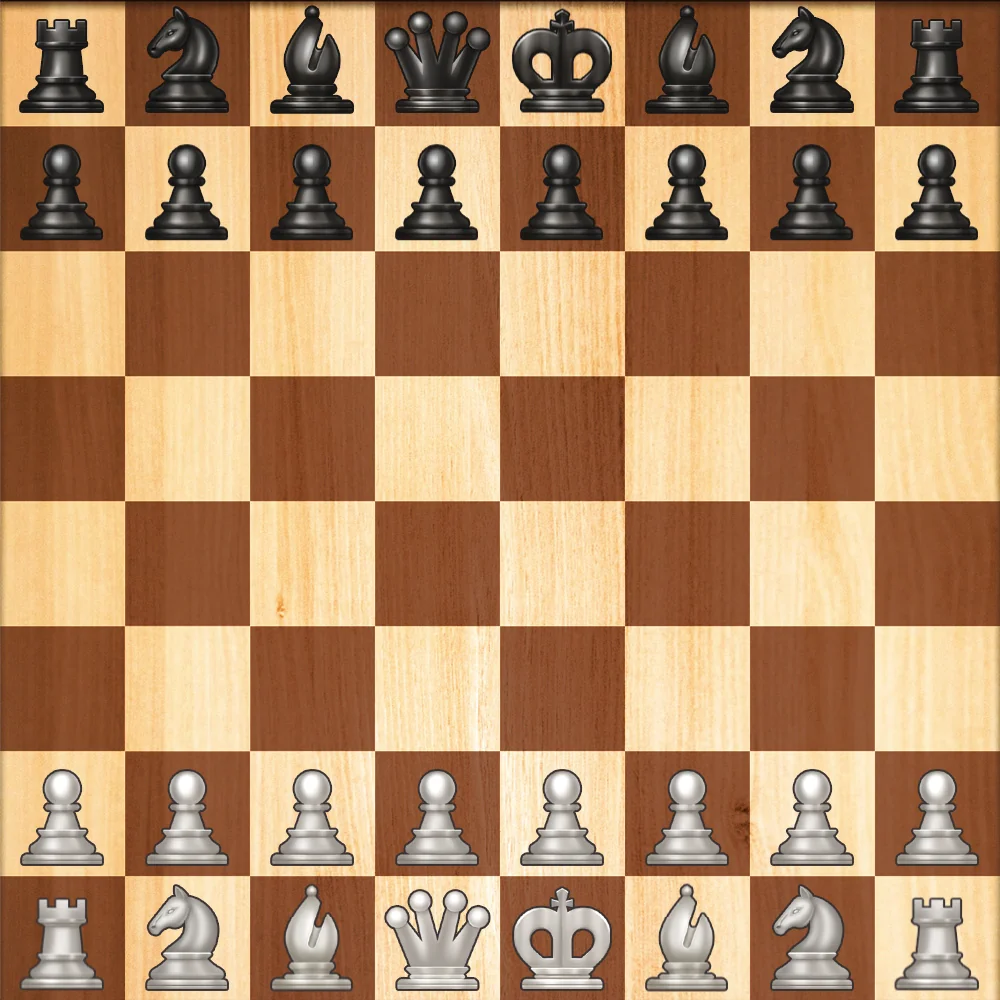

Starting the Game

White goes first. Each player in turn chooses one of his or her pieces and moves it according to the movement rules pertaining to that type of piece.

Capturing Pieces

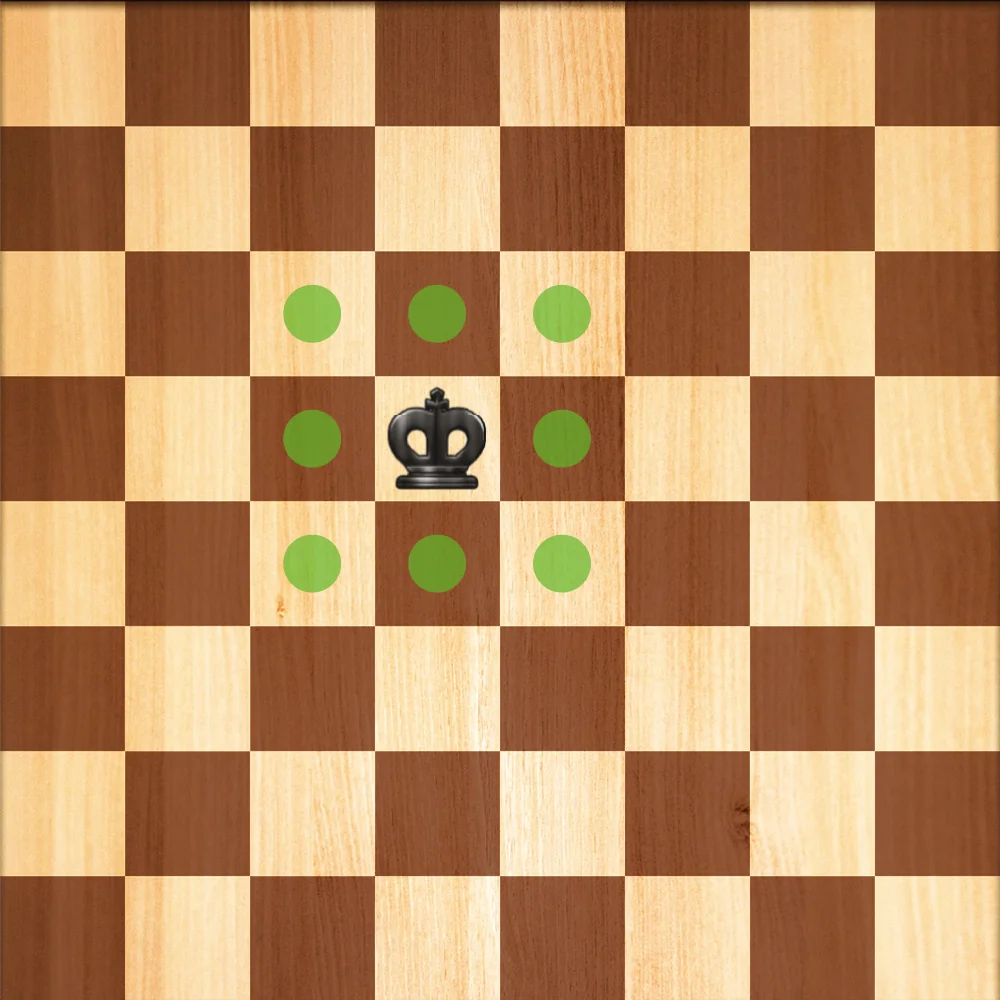

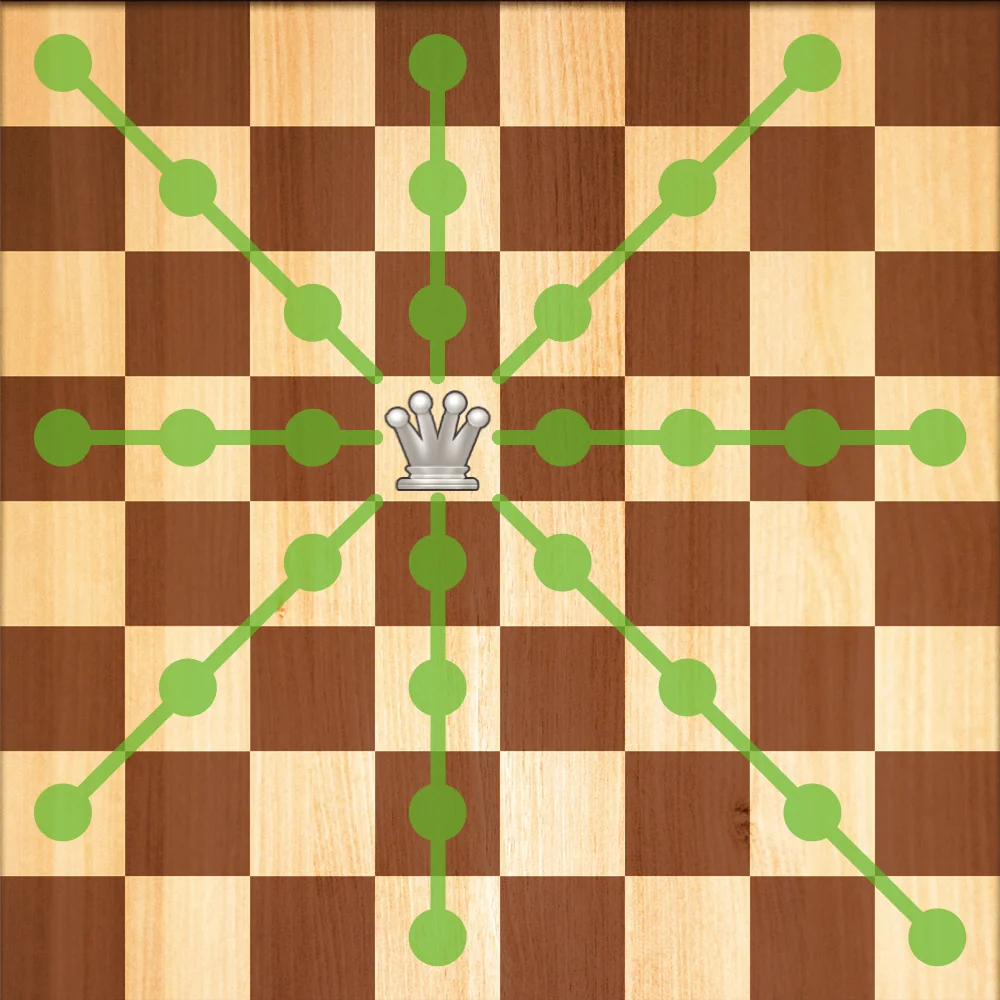

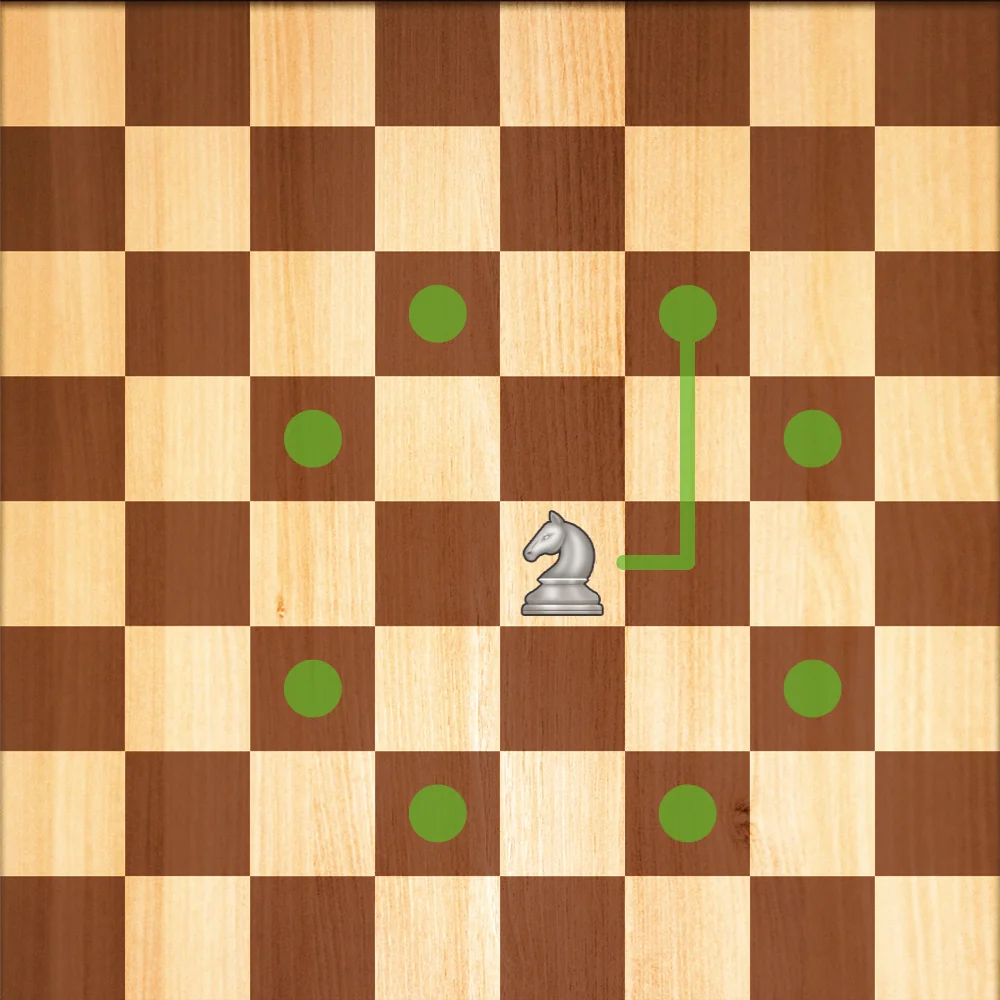

No piece may ever move onto a square occupied by another piece of the same color. A piece may, however, move onto a square occupied by an opponent's piece. When this happens, the opponent's piece is "captured" and is permanently removed from play. A piece making a capture must end its move immediately.

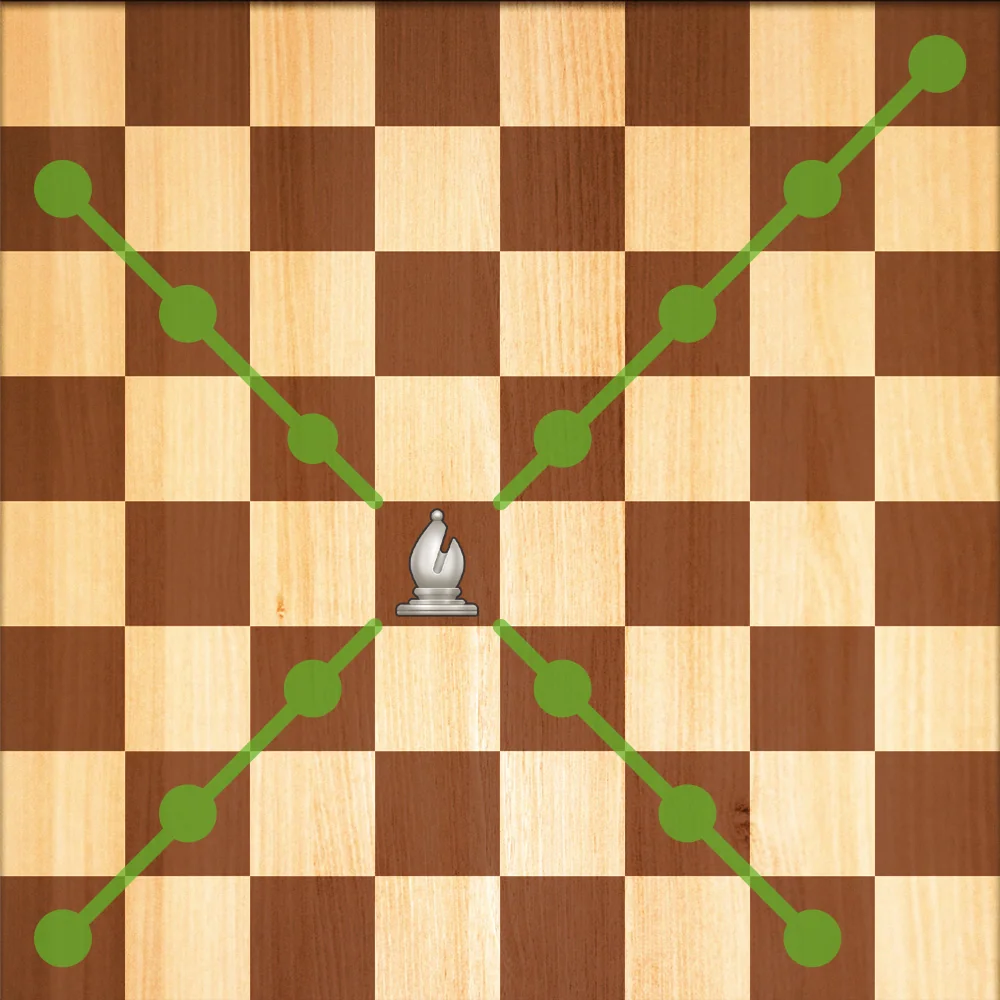

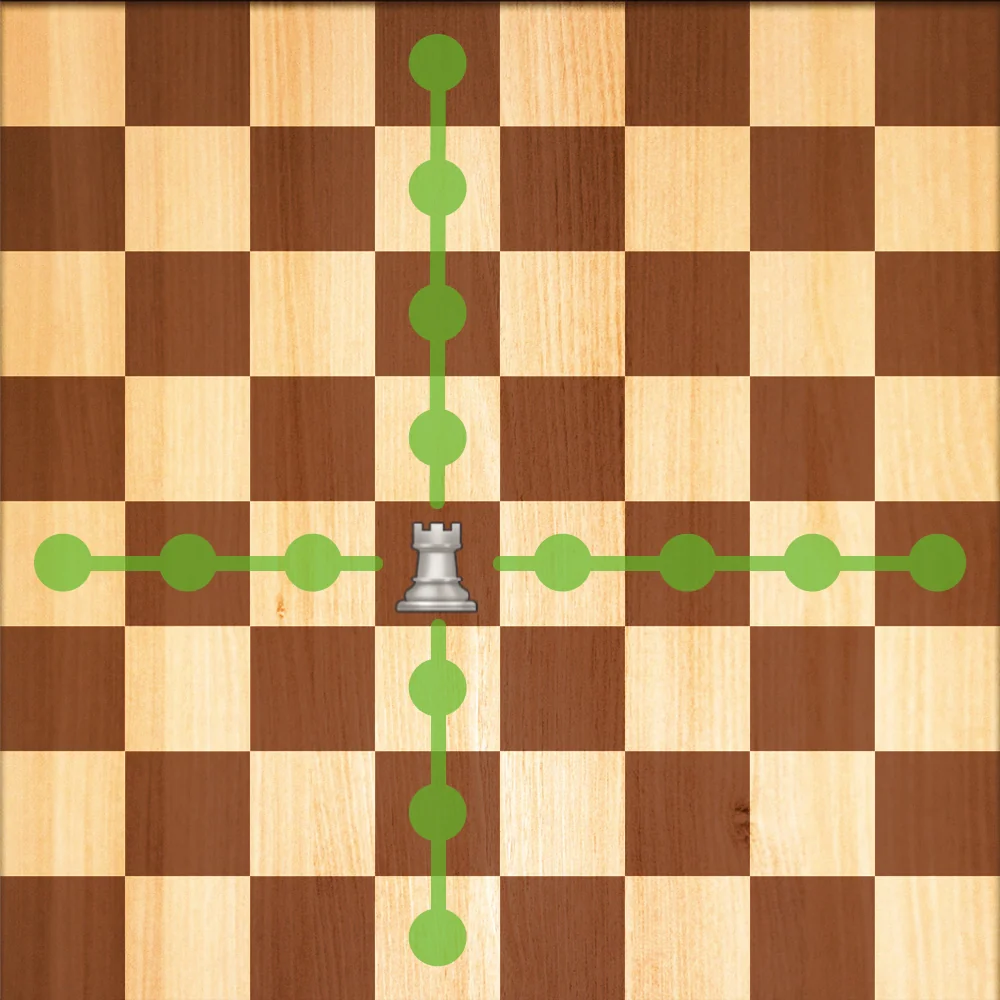

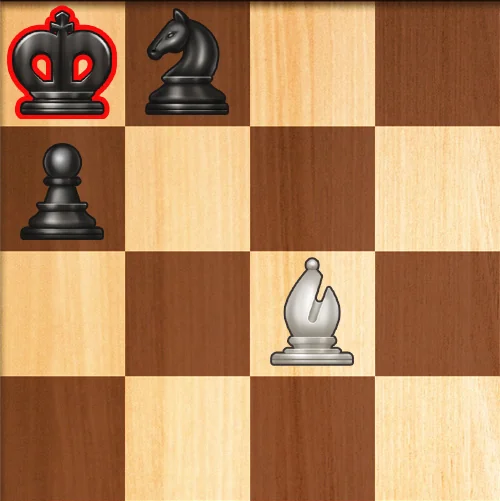

Kings, knights, bishops, rooks, and queens capture by moving in their usual ways, ending their move on a square occupied by an opponent's piece.

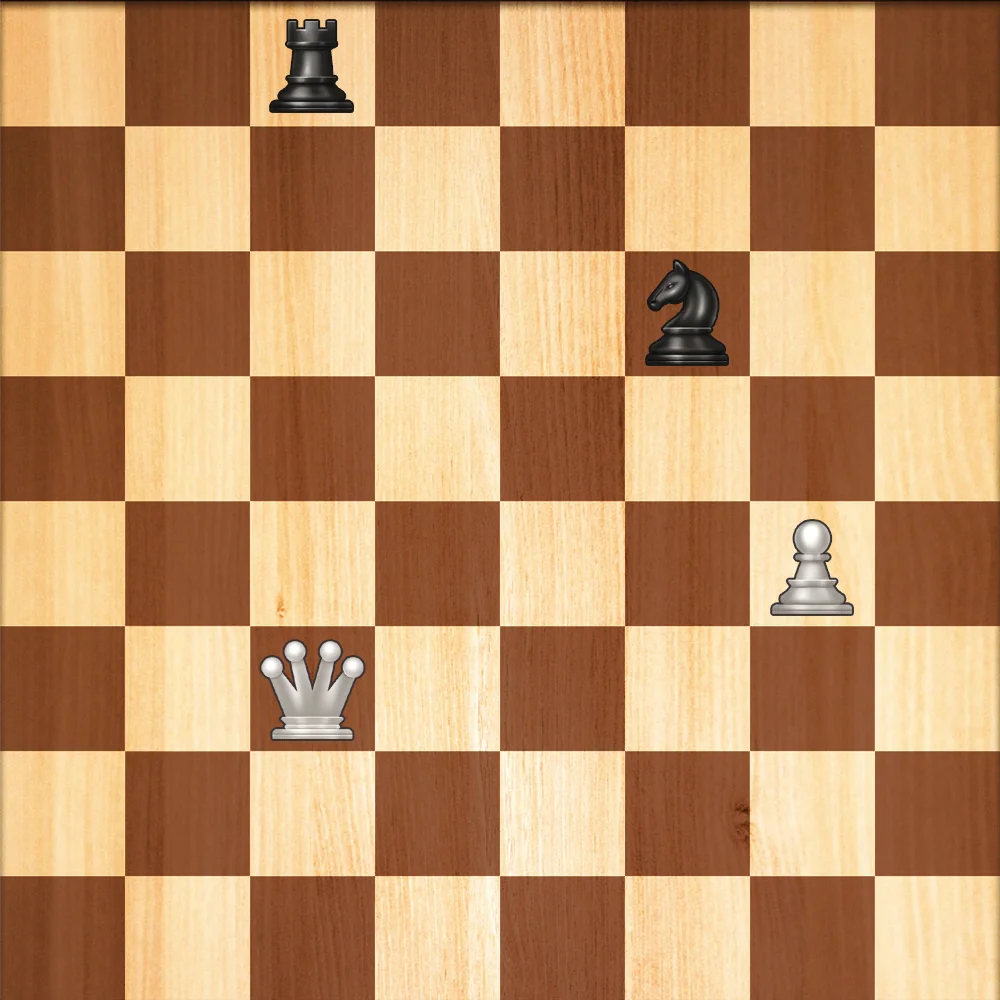

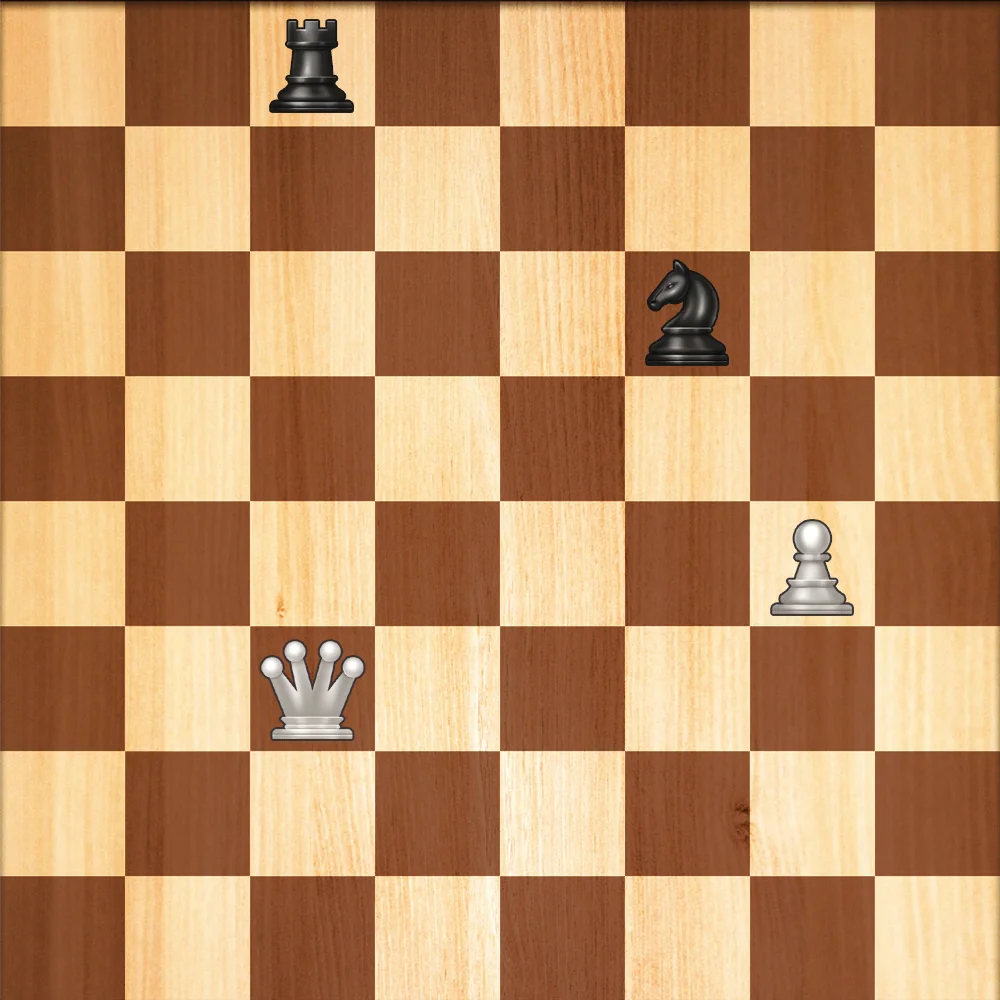

In the above diagram, the queen may land on and capture either the rook or knight, the rook may capture the queen, and the knight may capture the pawn.

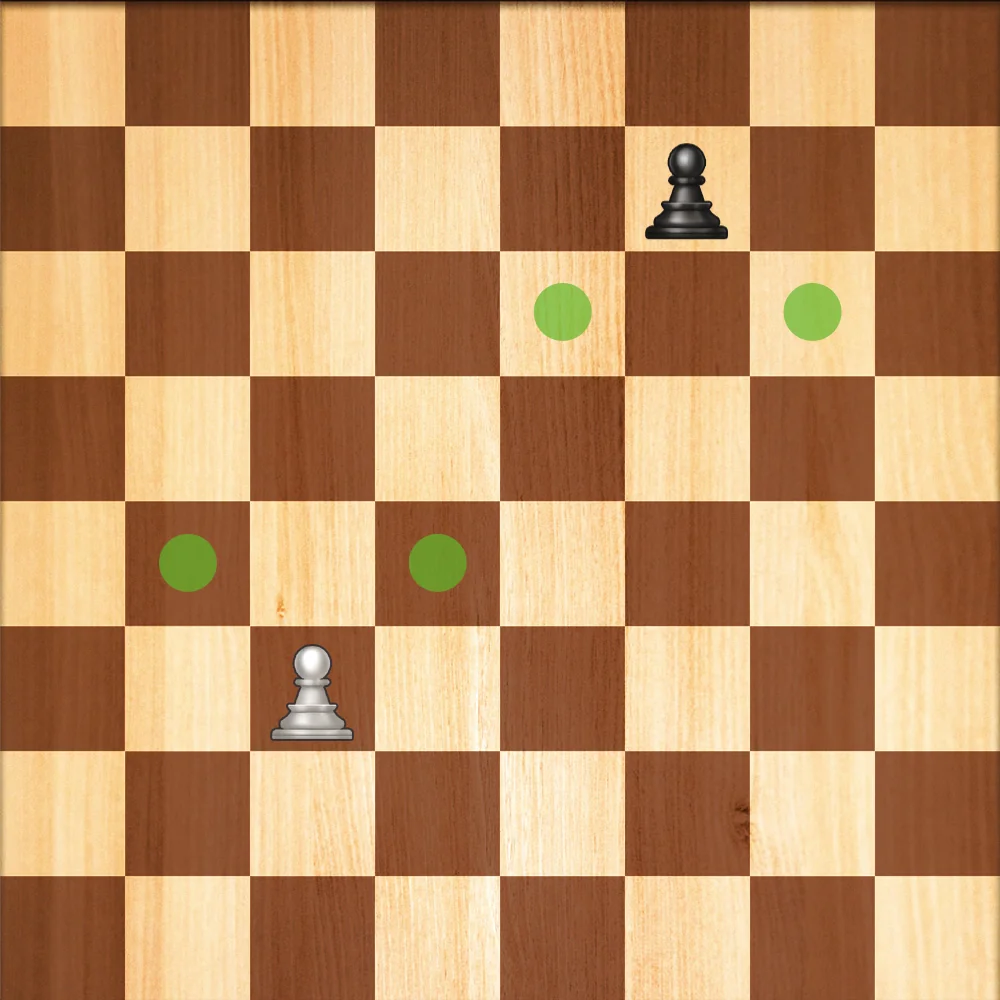

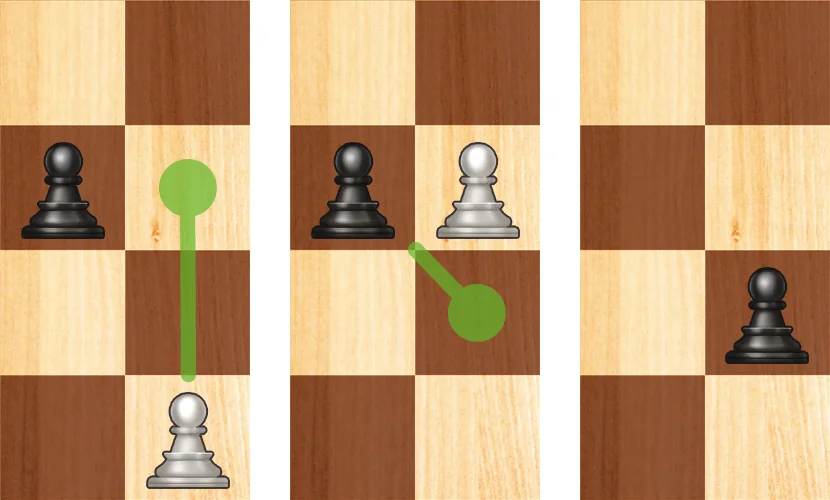

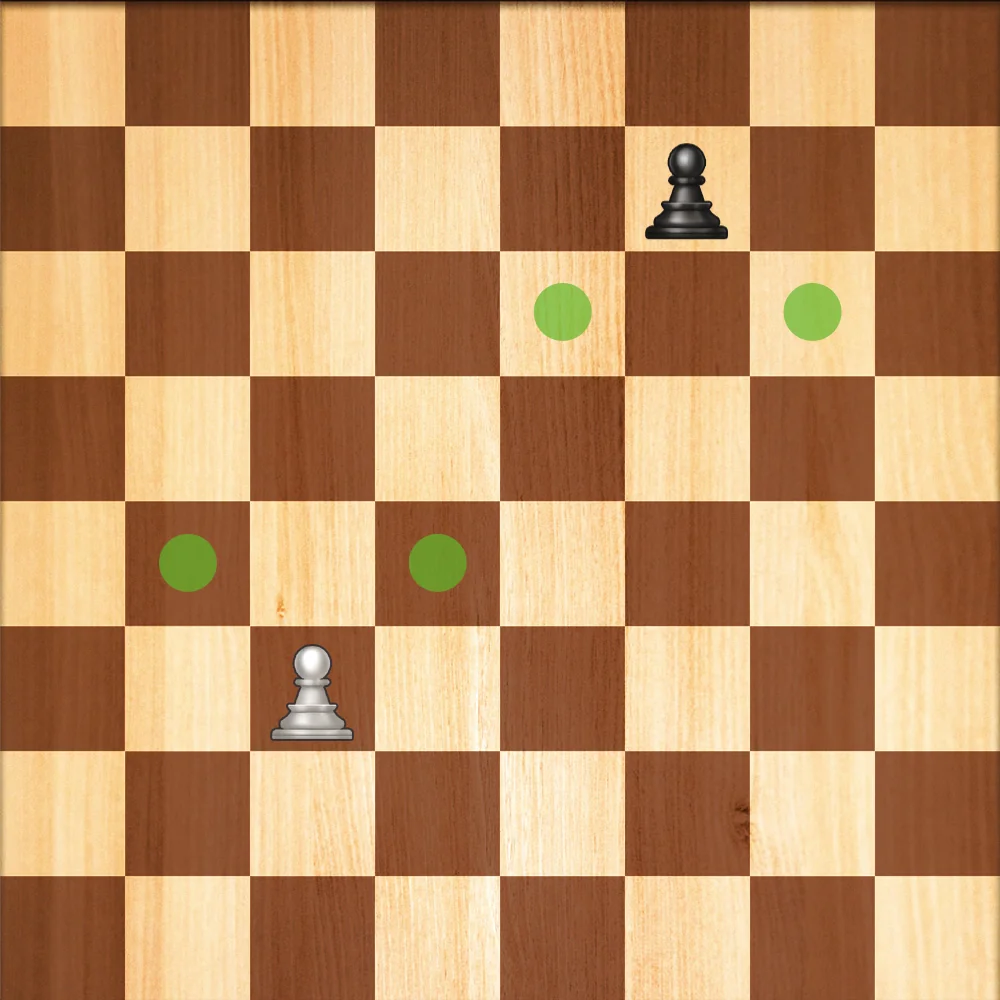

Pawns, however, do not capture as they move; instead, they capture by moving one square diagonally forward.

In the above diagram, the pawns may capture opposing pieces on any of the squares marked with green dots.

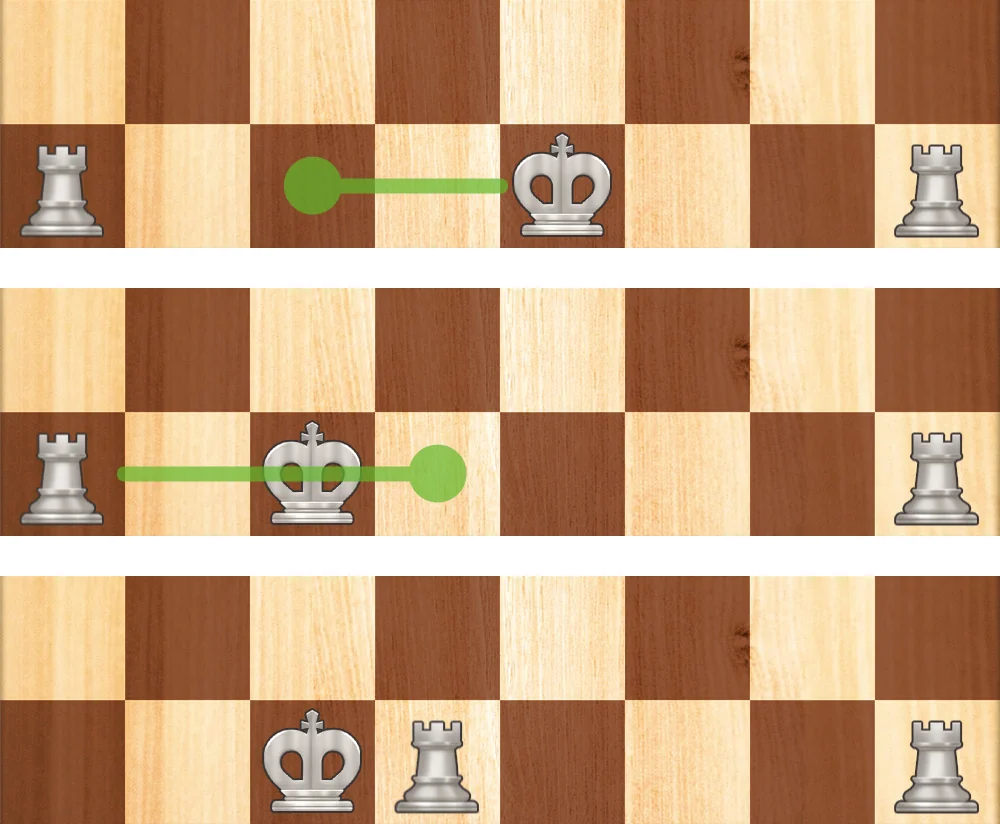

En Passant

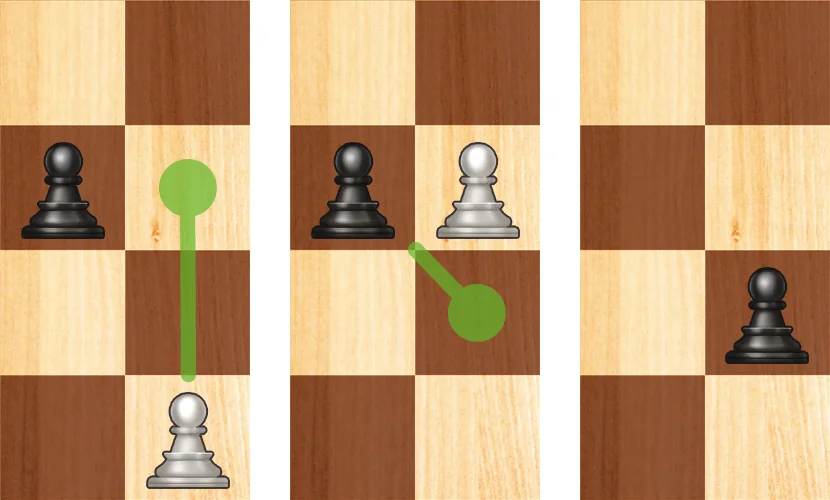

A pawn may also capture an enemy pawn "in passing," or "en passant."

This is only possible under the following conditions:

- The enemy pawn has just made a two-square advance from its starting square. (If it happened on a previous move, it's too late to make an en passant capture).

- A pawn could have captured the enemy pawn if it had only advanced one square instead of two.

When these conditions are met, the pawn may capture as if the enemy pawn had only advanced one square, as shown in the following diagrams. This is the only situation in chess in which moving onto an empty square results in a capture.

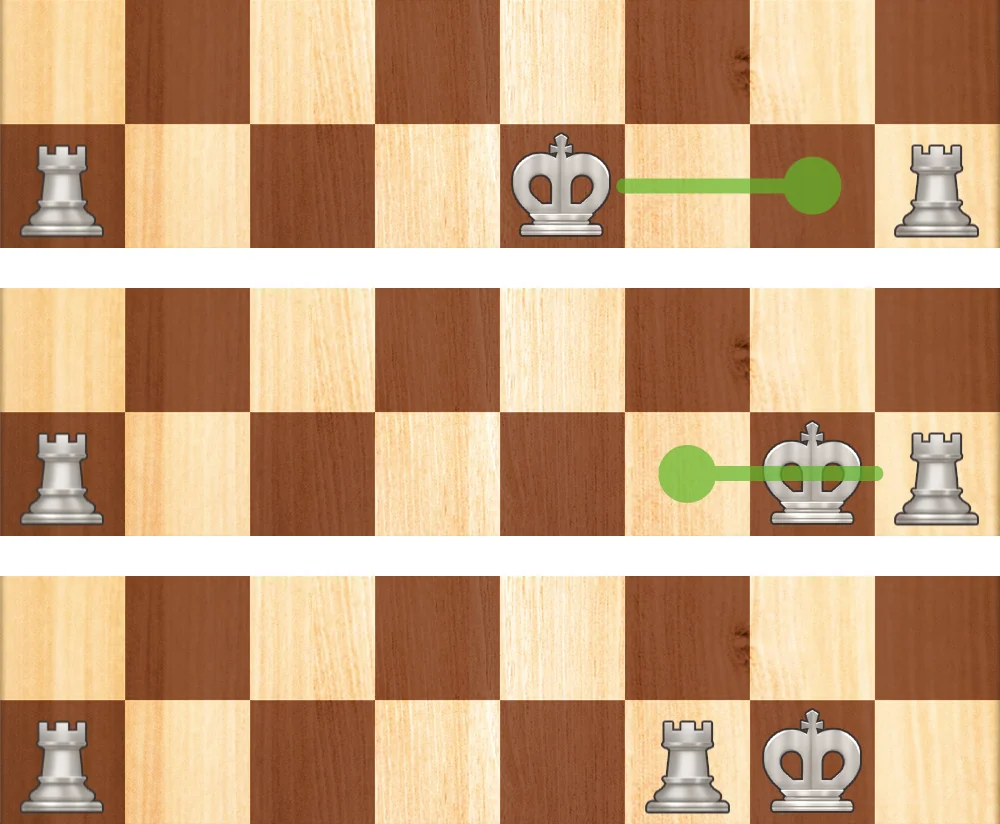

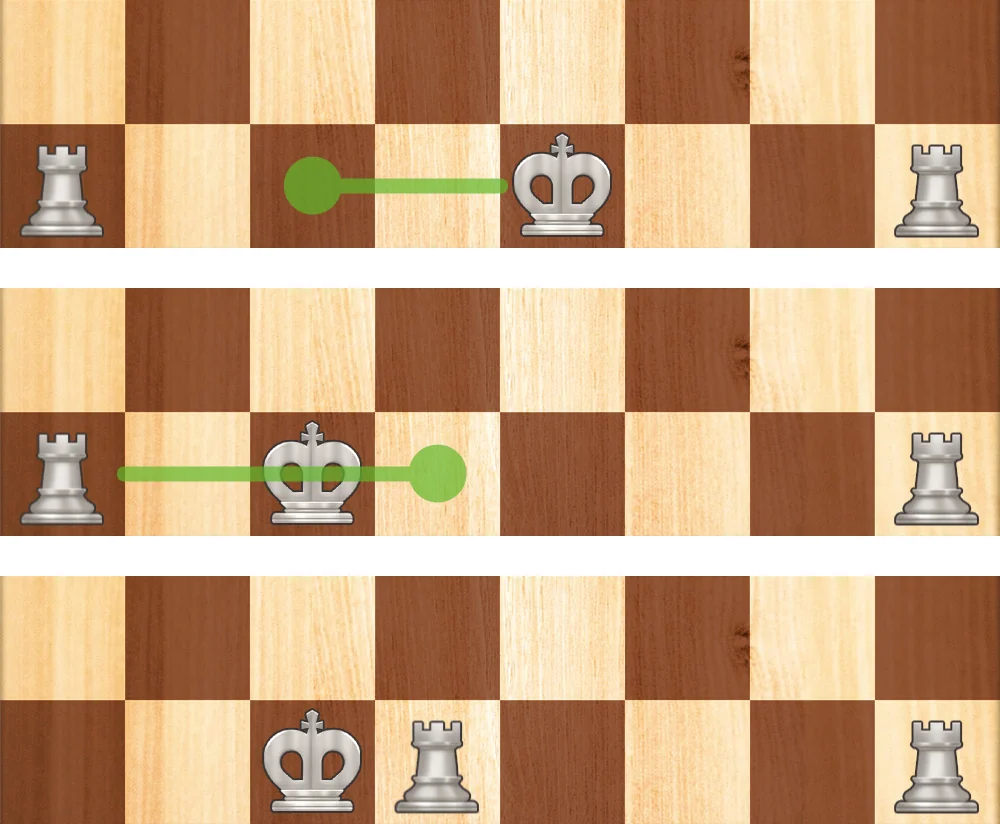

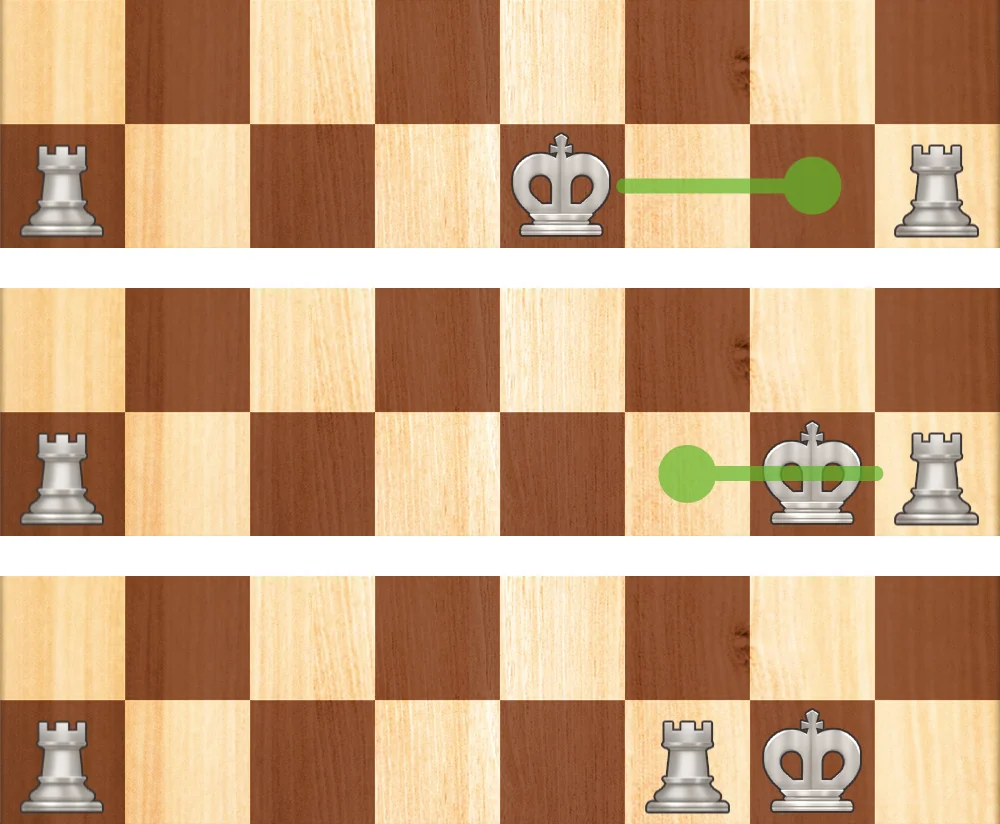

Castling

Once in the game, each player may make a special move called "Castling," in which both the king and one rook are moved. To castle, a player moves the king two squares toward either rook, then jumps that same rook over the king and stops on the square adjacent to the king.

For castling to be legal, the squares between the king and rook must all be empty, neither the king nor rook may have moved previously, the king may not be in check (under attack), and after the move neither the king nor the rook may be on a square that is under attack by an opposing piece.

Promotion

When a pawn advances to the last "rank," or horizontal row of squares, it is promoted into its owner's choice of a knight, bishop, rook, or queen (it may not become a king). The usual choice is a queen, the most powerful piece, and it is perfectly legal for a player to promote to a queen even though he or she already has one elsewhere on the board. Occasionally, it is better to promote to a knight (to fork two pieces or avoid stalemate) or a bishop or rook (to avoid stalemate).

Premoves

Premoves are conditional moves that are entered during your opponent's turn. This move is executed as soon as your opponent plays their move if your premove is valid at that time. If not, the premove is canceled and you must move normally. Premoves are most commonly used to save time on your clock. Premoves take no time off your clock in their execution.

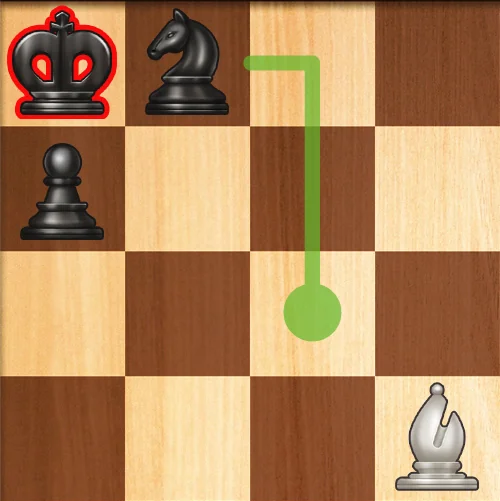

In the below image, the move highlighted in blue is a premove. The black pawn shown in the center of the destination square indicated that black currently has a pawn on that square. This pawn will be captured after black makes their move given that it is still a legal move.

Tactics

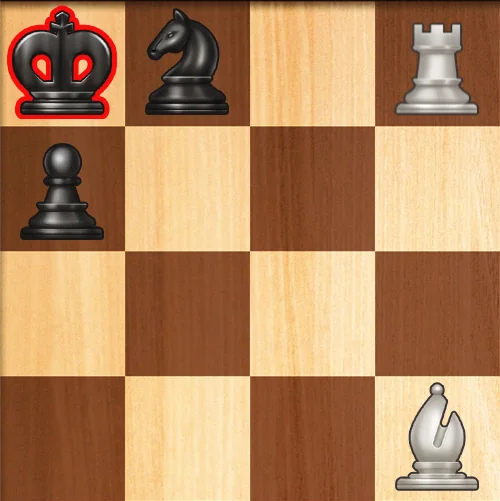

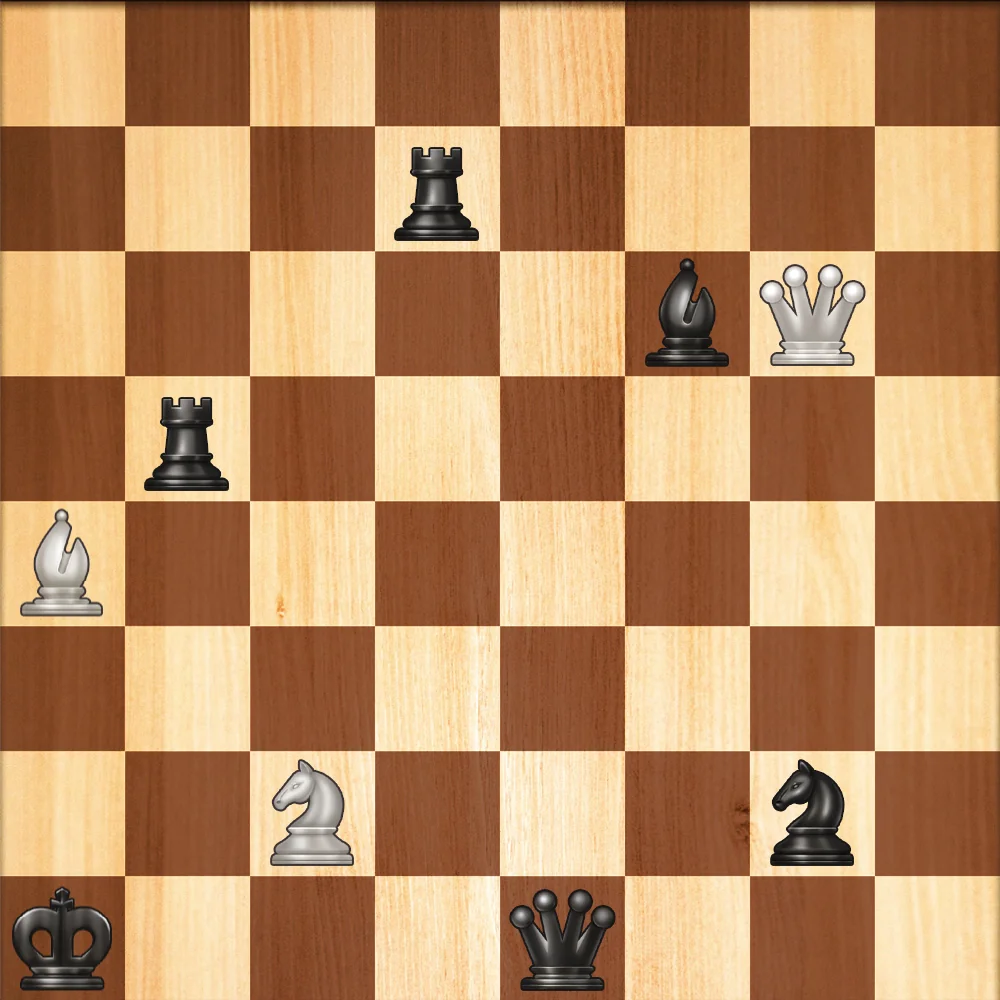

Throughout the game, players must be alert to the possibilities of combinations that win material or, occasionally, lead to checkmate. Forks and skewers are two of the most basic tactics; both involve attacks on two or more targets, not all of which can be defended.

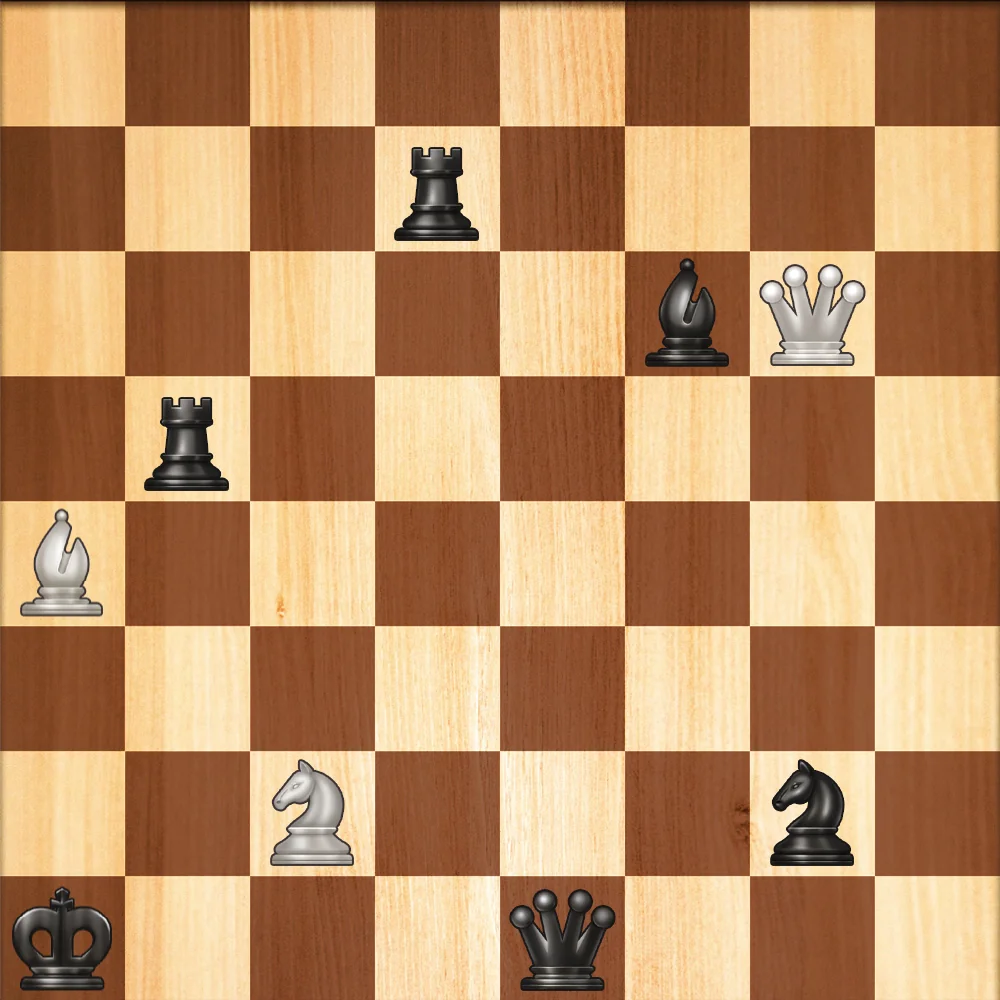

In the above diagram, for example, the White knight is forking the black king and queen, the White Queen is forking the bishop and knight, and the White bishop is skewering the two rooks.

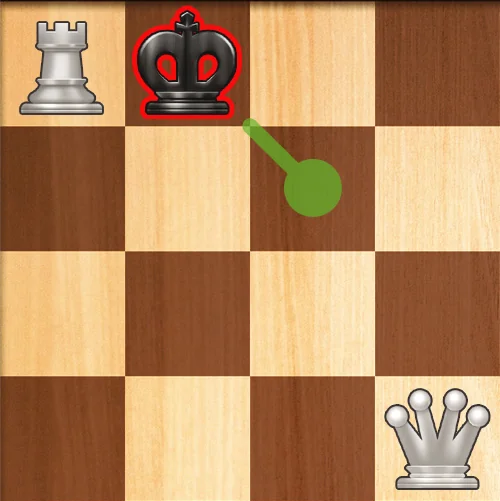

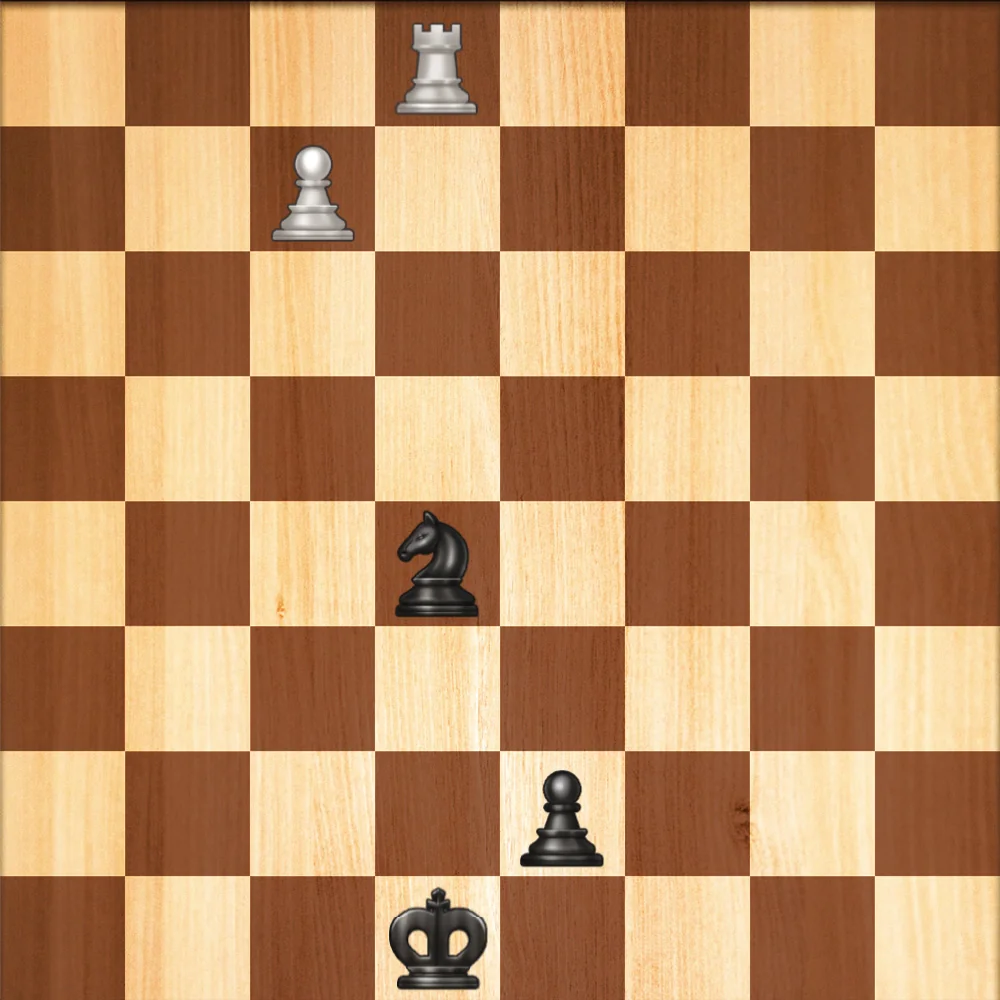

Pins are another common tactic for winning material. A piece may be pinned against a king or against another piece.

In the above position, Black's knight cannot move without putting the king in check. Even if Black defends the knight with their pawn, White can win it by playing their pawn forward two squares to attack it.

Common Openings

The most common opening moves for White are 1.e2-e4 (king's pawn opening) and 1.d2-d4 (queen's pawn opening).

Also popular are 1.c2-c4 (English opening) and 1.Ng1-f3 (which most often transposes into positions similar to queen's pawn or English openings).

Control of the Center

In the opening and for most of the game, players should attempt to control the four center squares, as well as the 12 squares around them. On an empty board, bishops, knights, and queens attack more squares when on a center square than when they are near the edge. It's equally important to get your own pieces to these good squares and to keep the opponent from doing the same. In most openings, each player will initially take control of the two center squares of one color.

For example, after 1.d2-d4, d7-d5, White temporarily has control of the dark squares, while Black has control of the light squares. The move 2.c2-c4 then challenges Black's light-square grip. Whether Black now takes the pawn or defends with e7-e6 (either move is good), Black must give a high priority to advancing a pawn to either c5 or e5. Other things being equal, if White is able to prevent Black from playing either of these moves, White will have a strategically won game.

Openings Tips

Generally it's best to move least valuable pieces out first, most valuable pieces last. The queen should not be moved out early, as it presents a target for the opponent to attack. If you are forced to move your queen repeatedly while your opponent develops several pieces, you will be in trouble.

Noncommittal moves should be made before committal moves. For this reason, the first nonpawn move should usually be with a knight, for which the best square is the easiest to determine. For example, when it's clear that your king's knight's best development will be to f3 (or occasionally e2), chances are you'll still be considering several possibilities for your king's bishop. By first making the move you know you are going to make, you can then take your opponent's next move into account when you move your bishop.

Don't move the same piece more than once without a good reason. Move one pawn to open a line for each bishop, but don't move many other pawns until your pieces are developed. Above all, fight for control of the center, as discussed above. If the opponent has advanced pawns to the fourth rank in two of the four central files, you must do the same to keep your share of center control.

Middle Game

Players should continually try to improve their position by taking control of open lines, attacking important center squares or squares near the opponent's king, and bringing their pieces to squares where they are most effective.

When your pieces have reached their ideal squares, and not before, it's time to move a pawn.

Every pawn move, even good moves like the advance of a center pawn in the opening, permanently weakens the squares that the pawn had previously defended. Unlike piece moves, pawn moves cannot be undone because pawns cannot move backward. It's especially dangerous to advance the pawns in front of your king's castled position. While it's common and reasonably safe to castle on a side where a bishop is fianchettoed, or where the edge pawn has advanced one square, a castle in which no pawn has moved is the most secure. Pawn moves around the castle should only be made when absolutely necessary.

Pawns can be advanced to drive enemy pieces from their best squares, to open lines of attack, and to exchange opposing pawns that are shielding the king or other pieces from attack. As pawns are moved and exchanged, players should try to keep their pawn structure as strong as possible. That means avoiding doubled pawns, backward pawns, and the creation of holes--squares that a player can never attack with a pawn, and which the opponent is likely to exploit by occupying with a piece, especially a knight.

In the middle game, players should analyze the position as objectively as possible to determine each side's strengths and weaknesses, then form a plan that takes advantage of their own strengths and exploits the opponent's weaknesses. A player with an advantage should attack, or risk losing the advantage. A player with a disadvantage should think defensively; attacking from a position of weakness is an easy way to lose quickly.

Here are a few other principles of middle game play:

The stronger your control of the center, the safer it is to expose your king.

If your opponent attacks on a wing, counterattack in the center.

Overprotect key squares, such as vital center pawns. If one of your pieces or pawns is defended by one more piece than is necessary to protect it, then each defending piece is free to move away, which means many more options.

After deciding on your move, before making it, give the board a final glance as if looking at the position for the first time--just to be sure you're not overlooking something major.

Endgame

In an endgame, an advantage of two or more pawns is usually enough to win routinely. With other things being equal, being a pawn ahead is usually enough to win when players have pawns on both sides of the board, but not enough when all pawns are on one side of the board.

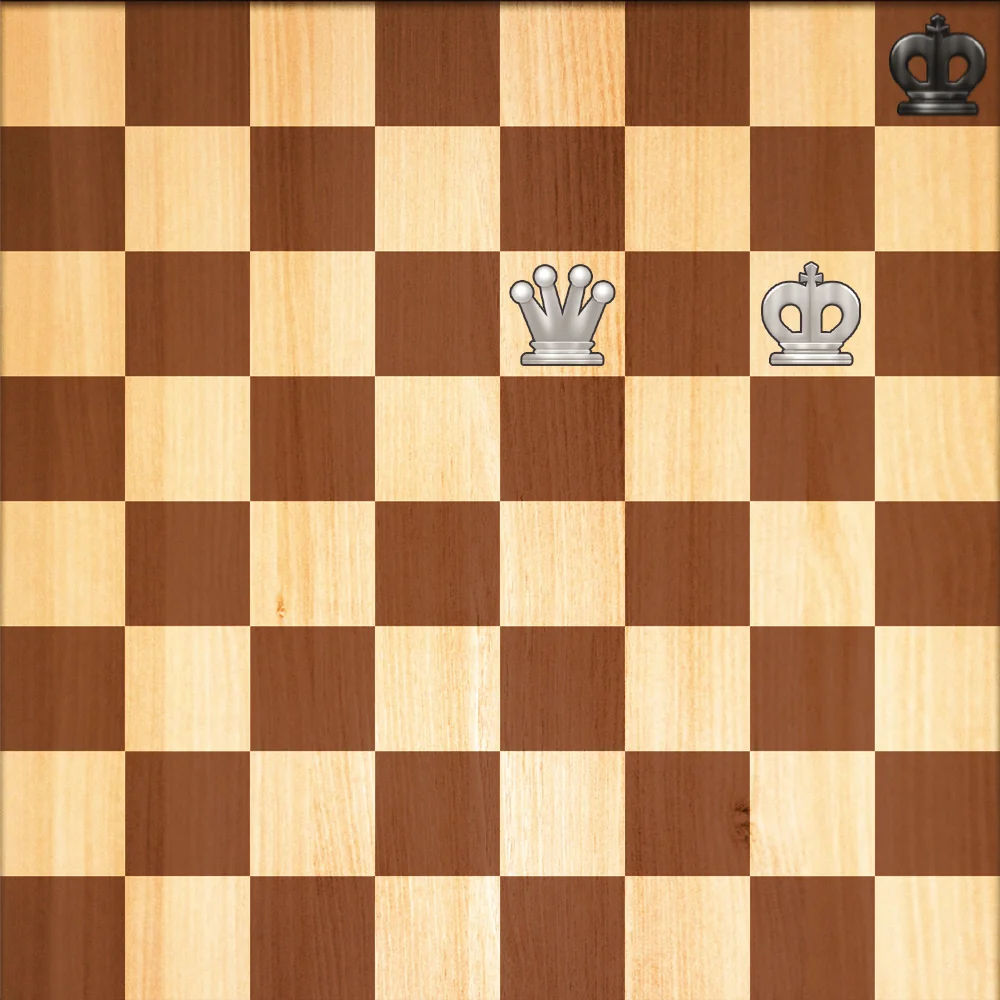

In endings with only kings and pawns, a crucial factor is often who has the opposition. This is similar to the concept of "the move" in Checkers. If two kings lie along the same line--a rank, a file, or a diagonal--with an odd number of squares intervening, the player who just moved has the opposition. In the simplest ending, king and pawn vs. king, having the opposition can mean the difference between winning and drawing.

Here are some basic endgame principles:

When you are one or two pawns ahead, exchange pieces but not pawns.

When you are one or two pawns behind, exchange pawns but not pieces, and try to eliminate all pawns from one side of the board.

Advance passed pawns as rapidly as possible.

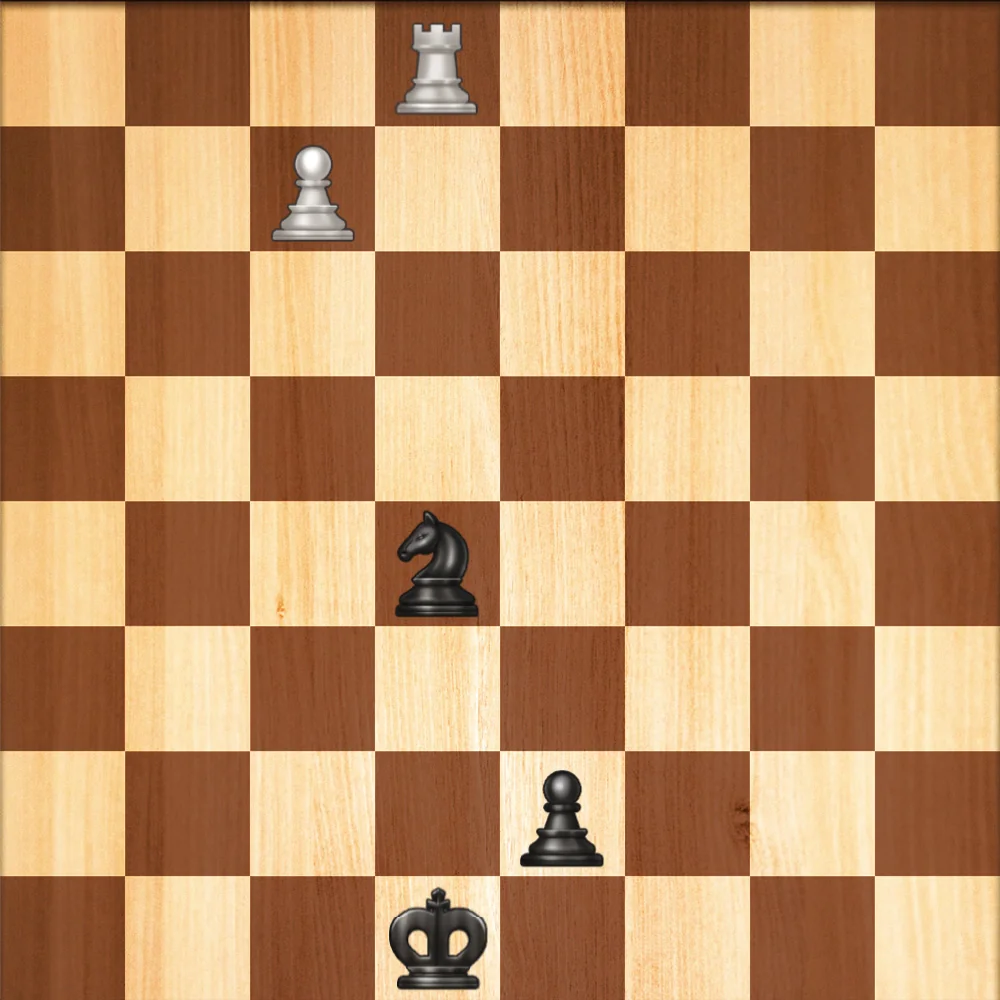

Place rooks behind passed pawns--whether the pawns are yours or your opponent's.

Endings in which players have bishops of opposite colors (one moving on light squares, the other on dark squares) are the hardest to win if you're one or two pawns ahead, and the easiest to draw if you're one or two pawns behind.

Endings with only kings and pawns are the easiest to win when you're a pawn ahead.

Chess

Chess